One join to rule them all

When it comes to databases, the whole is often greater than the sum of its parts. Creating a whole picture of customers is the next big data project for many established companies, and it's a task that's fraught with ethical and legal risk.

Imagine that you're a hotel owner. You know which of your guests stay with you, based on a loyalty program you run. But you don't know those guests' travel habits once they leave your lobby. If only you could join what you know about your customers with what others know, you could implement marvelous new marketing and support offerings.

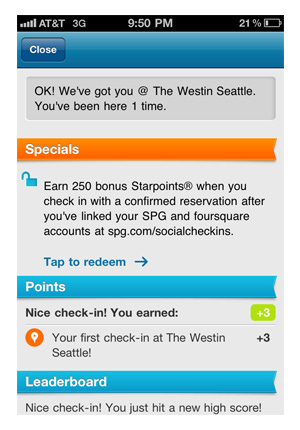

This isn't actually hypothetical. Recently, I checked in to the Westin in Seattle. Here's what Foursquare showed me:

The hotel chain was trying to convince me to link my Starwood (SPG) account with my Foursquare account. Doing so without permission, however, is increasingly frowned upon.

In the database world, the act of connecting two otherwise separate tables of data is called a Join. It links two sets of records—people and electrical bills, for example—by a value that exists in both tables, such as home address. This value, or key, is better the more unique it is. A first name isn't a very reliable way to join two tables, but a social security number is.

This Join is the foundation of many modern business applications. Customer Relationship Management (CRM) and Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) software, cornerstones of large enterprises, rely heavily on relational databases that link together tables of data in this way.

The next frontier for databases is linking public and private data—joining what a company knows about its customers with what the Internet knows about them. Applications like Google Latitude, Foursquare, Twitter, and Facebook Places know plenty about where people are. The challenge for enterprises is to link that information with corporate data without breaking the law or losing consumers' trust.

When we talk about data privacy, much of the time we're really talking about Joins that happen without our permission.

If you visit three different websites, you might think that your activity on each site is insulated from the others. But if those sites all use the same ad service, then the service knows what you've done on all three, as this excellent demonstration from Collusion shows.

When you visit several websites that use the Facebook Like button, you're ultimately helping Facebook to join your behavior across those sites, and in the end to get a better understanding of who you are and what you do. That's one of the reasons that Germany is banning the Like button.

Apple's recently revealed plans to cut off the unique device ID from developers in a future release of IOS will make it harder to know what device an app is running on. This is likely in response to security, tracking, and privacy concerns.

At the 2012 Strata Conference, Daniel Tunkelang asked a provocative question. If it's somehow unethical to infer private information from the commingling of publicly available data sets, have we established a new kind of thoughtcrime? Increasingly, privacy isn't about the data someone has on you as much as it's about their ability to process it.

As another speaker, who shall remain nameless, put it, "if I have more data about you than you have I can dismember you a finger at a time." Ouch.

Today, your privacy is directly related to how complete the great lookup table in the sky is, who can access it, and how easily you can remove things from it.

Marketing consortia hoard loyalty data today, sharing it among partners such as the Star Alliance group for travel. These Data Zaibatsu already collude—with your permission—to build a more complete picture of yourself. Now, however, they're rushing to expand what they know dramatically, harvesting the data exhaust of walled gardens. Ultimately, they'll know more about ourselves than we do, creating a far more precise picture than we imagine from the brush strokes of our daily lives.