What comes after the attention economy?

Channeling Herbert Simon to understand post-AI scarcity and abundance

It’s now really clear that AI is coming for a wide range of tasks for which we currently pay humans, particularly those in creative and white-collar fields. When I’m trying to understand where technology might take society, I try to channel my inner Herbert Simon.

Simon was a polymath, economist, philosopher, and computing pioneer. He wasn’t just really, really smart—he was good at good at seeing patterns others missed. If you’ve spent any time with me, you’re probably tired of hearing about him.

Back in the seventies, he observed that we live in an attention economy. His reasoning was as follows:

Economies are driven by what is scarce, and therefore valuable and in demand, such as arable land or industrial machinery.

Information is abundant and free.

Information consumes our attention, so when we have more information, we have less attention to pay to things.

Therefore, we live in an attention economy.

This was before the Internet, but there’s no better term to describe our online lives in 2023. When we talk about the attention economy, we usually refer to the platforms to which we devote a quarter of our lives: Discord, Twitter, Mastodon, Facebook, Google, and others that turn our engagement into money.

These companies have built complex technologies that keep us clicking, scrolling, and swiping, and they make money by pointing our attention at those who will pay for it in the form of advertising, product placement, and affiliate marketing. The industrial age had robber barons who owned the means of production; the attention age has Billionaires who own the means of distraction.

With the attention economy in full swing—and possibly even waning—what comes next? When AI and tools like ChatGPT, Dall-e and others are abundant and cheap, what becomes scarce? If information consumes our attention, what does AI consume?

Two kinds of attention

The word “attend” has two distinct meanings.

Directed attention

The first meaning of “attend” is to be present at something. When we attend one thing, we can’t attend another. We visit. We frequent, haunt, or hang out. We each have roughly 4,000 weeks of attention to direct in our lifetimes. Attention is a finite resource, there are 24 hours in a day, and it’s up to us how we spend them. There’s no way around that. Platforms need our actual eyeballs to pay the bills. This is the attention Simon was referring to: We take part in a thing.

Sidenote: Fake attention is a thing. A developer can write a script that pretends to attend something for us. Scammers and fraudsters create bots that pretend to be human all the time. Advertisers call fake traffic from bots click fraud: Using a computer to generate fake clicks that can artificially inflate site traffic, make a conference look popular, or drive likes and shares for a post. Ad-driven platforms go to great lengths to stop this kind of behaviour.

Attend to

The second meaning of attend is to deal with a thing. We have a matter to attend to. We need to manage, organize, or orchestrate something. We sort it out, handle it.

A computer that does this on our behalf is what we’re starting to call an AI. Whether that’s an expert system, automation, or actual machine learning doesn’t matter much: This is a computer script that attends to something on my behalf. Autoresponders, spellcheck, and search have been around for a long time, but in recent years the acceleration has been striking, and usable AI has finally broken into the public consciousness.

Sidenote: We currently take a “human-in-the-middle” approach to letting an AI attend to something for us. We review the final draft of something it wrote, or photoshop the fingers of something it hallucinated, or confirm the timing of the meeting it proposed, because we don’t trust the results yet. But as it gets better (and we get lazier) we’ll remove ourselves from the loop of such tasks.If the task is free to do, and of relatively low risk, we’ll trust the algorithm to handle it. The AI can make unchecked social media posts, because they cost nothing to publish, can be deleted, and (hopefully) won’t come back to haunt us.If the task is costly, or of high risk, we’ll want to be involved. An AI can tell us what kind of car to buy and how to negotiate, but we’re going to want to drive it ourselves and kick the tires before paying for it.Large Language Models like GPT-3 are trained on the sum of human knowledge. They can interpret a question pretty accurately, and turn it into something usable by a human, such as a tailored summary of a book, a personalized explanation, or a set of instructions for us to follow.

In other words: The Internet has given us a shortage of directed attention we can spend, but AI is now making attending to something cheap and easy.

Let’s talk about education

It’s time for a topic change. A future of education panel I participated in recently (embed at the bottom of this post,) focused on what learning, and testing, look like in an AI-augmented world. Since education is supposed to be preparation for a career, figuring out how education is changing might give us clues about how work will change, and what tomorrow’s economy might become.

How we know we know

Humans have have three main ways to measure whether someone knows something: Memorization, demonstration, and explanation.

Memorization

For factual recall, we ask students to memorize facts, and then regurgitate them accurately. Rote knowledge mattered much more in bygone days where the world’s facts weren’t at our fingertips; my grandmother knew the length of the world’s longest rivers and the height of its tallest mountains. I do not, but I can find out quickly.

Search pretty much destroyed this kind of testing. For a while, teachers banned students from using devices to look things up, but in a modern curriculum search is a tool to use, and students are instead taught how to search, and how to separate truth from fiction. Debaters and politicians learned to search for facts that supported their arguments; journalists learned to discern propaganda from the real story.

Demonstration

For objective understanding, we ask students them to demonstrate their knowledge by applying it.

Some things (like a math problem) are easy for a student to demonstrate:

The unit economics of testing a concept are very affordable. Whether you’re testing one student or one million students on a math problem, the total cost is roughly the same: Set up a Google form and share the URL; the materials are free. You’re asking for the student to deliver information as proof.

A single correct answer is easy to verify. If there is only one correct answer to a mathematical formula or a chemical equation, because we can assign a problem, the student can apply their knowledge to produce the result, and then we can check that result.

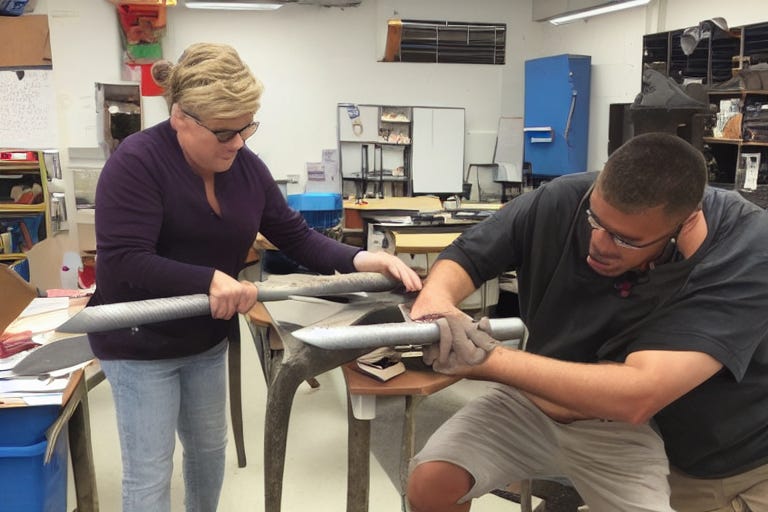

Other things (like forging a sword) are hard to demonstrate:

The unit economics suck. Each student needs an anvil, and bellows, and iron, and a hammer. Atoms are expensive, and the costs increase with the number of students.

It’s harder to mark the demonstration because there’s no objectively correct sword, so it requires judgement on the part of an instructor. Is the sword good? What does “good” mean? Context matters.

When calculators became commonplace, there was tremendous hand-wringing among teachers because math problems were no longer proof of knowledge. But as with search, the curriculum shifted to interpreting a problem, and figuring out how to use the calculator to arrive at the right answer.

On the other hand, demonstrating a physical skill (like sword-making) is still a great way to evaluate a student’s understanding. A search or an AI might give them tips, but there’s no subject for Fingerspitzengefühl, the perfect German word for “knowledge in the tips of the fingers.” Any technology that helps a student get better at the skill is just learning. Recipes aren’t cheating.

Explanation

For subjective understanding, we asked students to explain it. A reading comprehension test involved reading the whole book, and then providing a brief synopsis. As students advanced, we asked interpretive questions: What are the underlying themes? What are the main character’s motivations?

Just as pocket calculators changed how we tested math skills, and search changed how we tested factual knowledge, so ChatGPT will change how we test understanding. This is the specific form of testing educators are worried about today, because chatbots are explainers. As with calculators and search, educators will first try to ban these tools (using AI detectors, for example,) and then will gradually update their curricula to incorporate them (asking students to critique a ChatGPT response.)

What will now be scarce

In a world where calculators did the math, understanding the problem was what mattered. In a world where search knew all the facts, choosing the right facts mattered. In a world where AI can attend to things for us, summarize ideas, and generate instructions, three things become scarce: Prioritizing, doing, and novelty.

Prioritizing

By summarizing and attending to things on our behalf, an AI will give us a much wider range of ways to spend our days. Should we exercise (because our watch tells us about our steps and the pancakes we ate last night)? Should we learn to play music (because every phone is a recording studio)? Should we spend the day in immersive VR, or go for a hike in actual reality? Which of the fifty friends we’ve neglected should we call? Which interactions can be delegated to an algorithm, and which deserve our personal attention?

An abundance of options creates a poverty of choice. We’ll need to choose wisely.

This isn’t an easy task. Trading off short-term pleasures for long-term gains is a constant struggle for humans, whose brains are easily distracted by sugar, sex, and social pressure. It requires far more introspection than we currently teach: What does a child want to be? How will they contribute to society? How will they enjoy their life? We’ll want analytics, and feedback loops, and baselines. And of course, trusted curators and influencers to help us choose.

Setting great priorities in a world of distracting possibilities will become an increasingly hard challenge, and those who can do it best will win.

Outcomes

With so many things that can be done, we’ll value those who actually get them done instead of dithering. When AI can summarize and explain things for us is, what’ll be in demand are people who can interpret the things an AI suggests and produce something authentic, and unique, and tangible.

But not all outcomes are the same.

Any outcome that can be done for low risk and low cost (i.e. digitally) we’ll just hand over to the AI, in the same way we’re going to abdicate our calendaring and blogwriting duties to the algorithm. We’ll soon be awash in a million startup experiments, none of them real, all of them testing what colors, words, or prices work best.

Ffor the same reasons that it’s easy to test a math problem but hard to test swordmaking, humans who can turn AI inspiration into real-world results will be in particularly high demand. AI will talk the talk, but walking the walk will be rare. AIs can write the recipe; humans will bake the cake.

Schools will become onramps, because the startup you create for a business course or the science fair invention you demonstrate can quickly turn into an actual business or technology in a world where everything’s digital.

We’ll want outcomes.

Novelty

Imagine you’re standing in the foothills of the Himalayas. If you walk uphill, you’ll get to the top of a mountain. Unless you’re climbing Everest, you won’t be at the highest summit—in fact, you’ll have to go downhill to get higher. You’re standing on the local maximum, but not the global maximum.

Some mathematical functions have local and global maxima as well:

AI algorithms are always trying to run uphill. Midjourney is always trying to get better at rendering hands properly. ChatGPT always wants to provide better answers. They’re constantly optimizing by trying to get better at their core task (called an Objective Function.) That’s literally the “learning” part of machine learning.

But sometimes, to get higher up, you need to fall downhill for a while. You need to do something dumb, like getting sick of AI-generated art and making something out of cardboard and wool that goes viral. This is stuff humans are great at. We’re the fly in the ointment of the universe, the sand in the oyster of creativity. If AI is smart, we’re its muse. The model gets trained; we figure out what it missed. The algorithm predicts; we defy prediction.

What becomes scarce is novelty.

What do we call the next economy?

What comes after the Attention Economy? Some people have called it the “post-scarcity” economy, but with famine, climate refugees, and wars on the rise, that term’s not just wrong, it’s outrageous. Another term I’ve heard used is the “augmented” economy, and while all humans are definitely augmented by algorithms, that doesn’t really convey the scarcity that drives demand.

If Herbert Simon were with us today, I think he’d consider priority, outcome, or novelty worthwhile candidates for the economy that follows attention. An abundance of AI attending to things will create a poverty of prioritization, tangible outcomes, and algorithm-defying novelty. If you’re a startup, how are you building towards one of those economies?

Postscripts

If you want to see it, here’s the Learning Planet discussion.

Clickbait is unreasonably effective, and we already live in a split test. This video from Veritaseum is well worth your time.

Simply being able to prioritize things is

It’s is an incredibly privileged conversation. Many people won’t get to choose. Front-line workers, migrants, and marginalized groups will stand on the other side of the digital divide that AI creates, and demand to be let in.

Algorithms are already choosing what we see in our feeds and what notifications we receive. AI is being used on us, not by us. Any free AI will need to make money from advertising, collecting personal information, and training its model. If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. The truth is paywalled but the lies are free.

AI can help us make more efficient use of our time, even if it can’t attend things on our behalf. For example, there’s a range of meeting tools that will attend, record, and summarize meetings for you, such as Supernormal, Rewatch, and Otter.ai. These work in business settings, and you might be able to skip a meeting and read the summary. But that’s not the “attention economy” to which Simon was referring.

On the educational front, tech is moving the “real world” line, because many things you could only do by hand can now be simulated. A chemistry lab is dangerous and smelly, but you can simulate chemical reactions on a tablet. A field trip is costly, but you can take one in VR. The University of Boulder, Colorado has hundreds of physics, chemistry, and biology simulations that let students experiment in simulated environments. Want to stimulate a neuron? Go try it now!

Loved this, thanks Alistair.... If we were to consider the civil disobedience against attention manufactured platforms, models and tech., would you consider something along the lines of 'The Liberation Economy' working?