We aren’t thinking weird enough

What the great flip means for us

Science fiction authors like to start with the world as we know it, and then change one aspect of that world: Aliens exist; time travel is possible. These stories tickle our brains because they dwell on how one fundamental shift has widespread consequences, creating a world almost unrecognizable from our own.

Imagine that one day, you woke up and a universal constant had changed. Maybe the speed of light was slower; maybe gravity had been cut in half. Assuming you were even still alive, your world would be vastly different. Buildings might collapse; or things might fly away into space. Time would pass differently. Changing a fundamental constant would upend life as we know it.

Photo by photo-nic.co.uk nic on Unsplash

So why are we surprised that completely altering a fundamental law of communication has had a similar effect?

In the last decade, we’ve made it possible for anyone, anywhere, to send anything to everyone, everywhere, for free. I call this The Great Flip: Once, you paid to get people to watch. Now, if you can get people to watch, you get paid.

This flip has upended every political and business system we take for granted. This shouldn’t surprise us. But we’re in the midst of it, and we can’t see the forest for the trees. We need to acknowledge the scope of this change, and understand that it’s forcing a complete recalibration of society and business.

Everyone, everywhere

The top-performing 2019 Superbowl ad reached 50 million viewers.

A 2019 Superbowl ad cost $5.25M for 30 seconds. That means that with traditional broadcast marketing, we pay $0.109 per viewer.

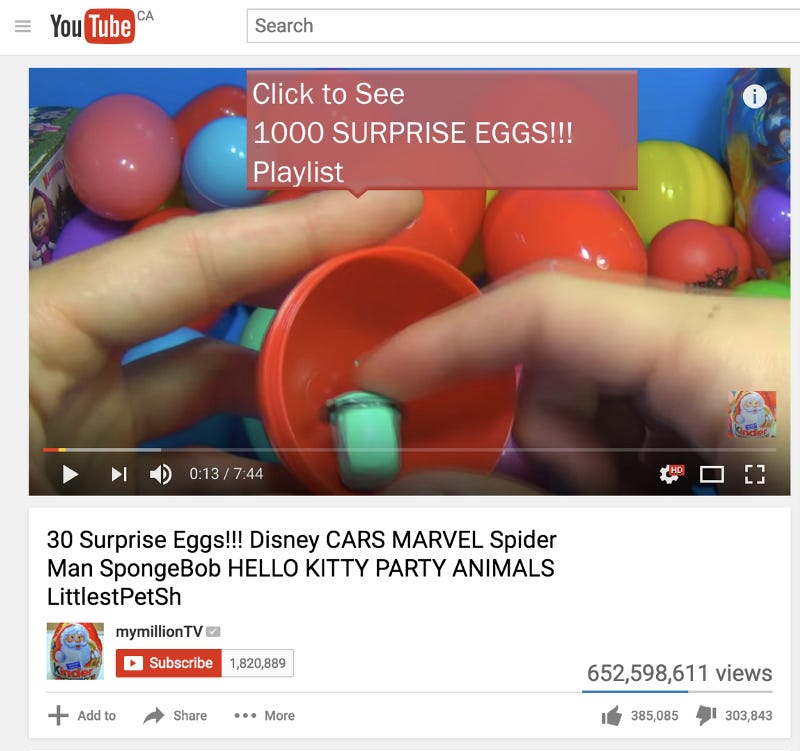

This Youtube video has 652,598,611 views. Even assuming that each viewer watched it 5 times, that’s still 130,519,722 people. At Superbowl rates, that would have cost US$14,226,649.70.

But that isn’t the new economics of media. Publishers lament the collapse of revenues because content is free—but they’re wrong. Youtube pays for views.

Shelby Church, a prominent Youtuber, recently shared that she made $15,000 from a YouTube video with 4.1 million views. Amounts vary based on engagement, time spend watching, and myriad other factors. But using Shelby’s math, that’s $0.003658536585 per view. So the egg video above would have earned its creators $477,511.18. And its production costs are almost zero.

That isn’t “free content.” That’s a complete reversal of information economics. A big flip: Instead of paying $14M, you make half a million. Again, once, you paid to get people to watch. Now, if you can get people to watch, you get paid.

The death of current political systems

The framers of the US constitution were trying, in 1776, to build a more perfect union. They drew from ideas of parliament (founded in 1215 on the creation of the Magna Carta.) They set up checks and balances in a tripartite tug-of-war. They created representation both of states (like-minded groups) and of populations (individuals.) And this model has served us well.

But around the world, that model is under attack. Politics is at its root a battle of ideas. The friction and cost of information is far lower than it was when the framers of the constitution put their ideas onto paper. And the and vulnerability to misinformation is far higher.

Consider, for example, just one aspect of how much has changed since that time: The number of citizens each member of Congress represents:

Number of citizens per representative over the last 200 years. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_congressional_apportionment)

The population of the planet has literally doubled in the last fifty years. This misrepresentation cannot stand.

That’s only one example of how modern politics is outdated. We’ve always tailored our speech to our audience. But targeted information at a global scale is entirely new. That’s what Sacha Baron Cohen means when he says, “Freedom of speech, not freedom of reach.”

Sacha Baron Cohen on the impact of social media on liberal democracies.

Each of us has a custom news feed, tailored to our interests, reinforcing our filter bubbles, increasing our conviction that we, alone, have the answers; that we belong with our tribe. The result, in most liberal democracies, is polarization, and an inability to work together for the greater good or to tackle our most pressing problems like disarmament, climate change, education, and disease.

The historian and economist Herbert Simon said that to understand an age, we must ask what’s scarce. Living at the dawn of abundant information, he observed that what information consumes is our attention: We live in an attention age.

In an era of abundant algorithms, we must ask what it is that algorithms consume—and I think it’s the truth. Algorithms can generate speech that’s close to human writing given only a couple of sentences, and flood otherwise civilized discussions. Deepfakes can make it look like anyone is saying anything. Dsinformation is easy: For every citizen able to think critically enough to detect the falsehood, ten will share it, overwhelming truth with noise.

We should not be surprised that current political systems are failing us. For them, gravity changed. It will take nothing less than a complete reimagining of government to find a new equilibrium.

The end of persistent externalities

A wise Wall Street executive—who wants to remain anonymous—once told me, “a hedge fund is an organization designed to find something that will one day be illegal, and to do it until it is.”

There’s a truth to this. Unreasonable profits are the result of externalities—uncaptured costs or subsidies that a business receives. Companies are due a profit for the value they add in creating and delivering products and services to consumers, but unreasonable profits come from a burden they impose on society that isn’t factored into their balance sheets. Oil companies don’t pay the monumental cost of climate change, so their margins are high.

Here’s an example.

If two similar drivers pay the same amount for car insurance, but one drives every day and the other only occasionally, the frequent driver enjoys an unfair subsidy. The insurer can only bill by time, but the drivers incur risk by the amount driven. This is an externality—and it exists because we are imperfectly capturing the cost (risk) of driving. Once an app can insure per mile, rather than per month, the externality vanishes—and such technologies are already on the market.

A connected, sensored world exposes externalities big and small. Aerial satellite imagery, once the domain of spy agencies, can be used to find Greek tax-dodgers who lie about owning a pool. Cheap sensors can measure pollution (capturing information on the conditions around them, or even how often asthma sufferers use their ventilators) and building a map of air quality.

The list of ways we can quickly detect an externality is long and growing.

But it isn’t just financial anomalies. Most businesses aren’t just judged by just their balance sheet. S&P subsidiary Trucost is just one example of the hundreds of companies that measure businesses on three additional dimensions: Environmental Sustainability; Social Impact; and Governance. It takes one photo of pollution, one hashtag, or one whistleblower to erase millions from a company’s balance sheet overnight.

In other words, a connected world with zero-cost information sharing eliminates the sustained externalities on which yesterday’s fortunes were built. It’s no wonder that the lifespan of big companies on the S&P and F500 has plummeted in recent decades.

For them, the speed of light changed.

What comes next?

For society, this means a complete rethinking of politics. What would a group of twentysomethings, unaware of how governments worked today, come up with? Would our leaders rule because of likes and upvotes? This is the realm of science fiction—but that’s the only place we’re going to find what’s next. We assume that representative democracy is the norm, but for most of humanity across most of history, it is the exception.

For business, this means the end of unreasonable profits and the rise of transparent authenticity. Companies have only two real choices: Share more of their business models, and adapt to public outcry; or to support kleptocratic monopolies that help them achieve profits far beyond the value they introduce. They’ll get called out; expect misinformation wars, cancel-culture consumerism, and a battle for truth.

The bottom line is that the fundamental constants of information economics have changed. It’s like waking up to discover electricity doesn’t work any more. We may or may not survive, but whatever the future looks like, we aren’t thinking weird enough.