The dawn of fake retail

How making it easy to create thousands of products will change branding and trust in retail

Scarcity and abundance are inextricably linked. When something is scarce, we protect and value it; when it’s abundant, we treat it recklessly.

Scarce and abundant tech

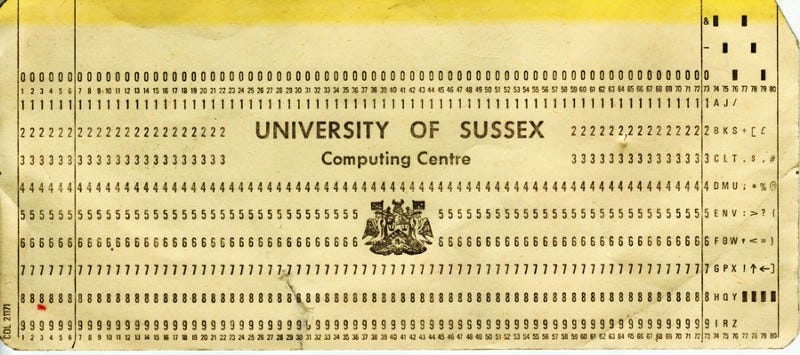

In the early days of Information Technology, a mainframe was precious. Students stayed up until the middle of the night to feed punched cards into the machines, knowing that with a single error they’d have to start all over.

Punched Card by Chris Limb on Flickr (https://www.flickr.com/photos/catmachine/3664956027)

Today, we discard our mobile phones when they get slow, and complain when Google takes more than a few seconds to search the sum of all human knowledge, for free. Tech isn’t precious; it’s nearly disposable.

When things get abundant, we don’t value them. And as Herbert Simon said, that which they consume becomes valuable.

There’s a new abundance on the horizon: The automated creation of digital goods, practically for free. Two recent examples suggest some very weird economics as bots and automation become commonplace—and some new value for that which they consume.

Spotify’s fake artists

Spotify, with hundreds of millions of listeners and a low barrier to entry for artists, is a perfect example. Scammers clone popular songs, so you’ll find dozens of results for one song, listen to a knock-off, and line the coffers of a plagiarist.

There are musicians who record Happy Birthday with every possible surname—Happy Birthday Matthew has been played over 400,000 times.

Today, making a song takes time. But with modern speech synthesis (which can reproduce voices almost indistinguishable from the original speaker), code can generate songs and flood the virtual bins of a streaming service. Here’s Lyrebird making politicians discuss Lyrebird:

Coming soon to speakers near you: DIY political debates that won’t burst your filter bubble.

A Bot starts selling phone cases

Someone unleashed an algorithm on Amazon’s marketplace, generating hundreds of iPhone cases that don’t exist. Most of the really egregious ones are gone now (but the link above has some examples.)

Who doesn’t want an orthopaedic compression bandage phone case?

This was probably done manually, with some automation. But an algorithm could easily find free stock photography on Unsplash or Flickr; use some kind of image recognition to label the image, and then create a listing for that case on Amazon. The friction of creating products has vanished.

Digital content is vanishingly cheap to distribute. With algorithms that can interpret images, mimic voices, create SKUs, and more, it will soon be vanishingly cheap to create and customize.

Forget Fake News; welcome to Fake Retail

The real problem consumers face with this abundance is trust and curation. It’s hard to find what you’re after when an army of bots is trying to tailor their latest knock-offs to your desires. It’s hard to find serendipity. We’re all on a curve, and we’re all being overfitted.

Trying to watch John Oliver

Many Canadians who’ve wanted to watch popular shows in Canada quickly discover that their favorite programs—SNL, John Oliver, etc.—aren’t playable here. To satisfy our Northern Appetites for liberal news media, as soon as a show airs, armies of uploaders put it on YouTube, taking steps to circumvent copyright detection:

Sometimes they crop the frame

Other times they play the first couple of minutes of content, then splice in something unrelated.

Sometimes the video is just a still image with audio.

A cropped screen and an upload gets you 158K views.

YouTube is a great petri dish of falsehoods. Now imagine this leaking out into every retail interaction you have.

No strong incentives to stop

It isn’t clear that retailers want to fix this. For Amazon, YouTube, or Spotify, more plays and more streams mean more money. On a streaming platform there’s even a chance more streams from unknown artists means less payouts for musicians, something Spotify is currently accused of.

But will consumers prefer curated brands?

What do we now value?

The death of the genuine article makes curation and provenance precious. Kevin Kelly talks about this when he urges creators to focus on veracity as a strategy. But at some point, the business value of curation will become far more significant than it is today.

You might think that ratings systems would help here, with buyers, consumers, and listeners flagging knock-offs. But that takes work, and humans are lazy; on one gigantic social network that allowed readers to flag bad content, the team told me that half their engineering money went into combatting bots and automation anyway—and this was nearly a decade ago.

This also means that app stores and online markets can’t simply scale through automation. They’ll be in an arms race that looks more like anti-spam, and they’ll be judged by the ratio of good to bad content.

The Apple app store has tighter curation, and users can’t circumvent the store by sideloading the way they can on Android; this is arguably a strength, and may be a reason that Apple makes more from its app store than Google, HTC, Samsung, or the other players in the Android ecosystem.

Electronic accessory maker Anker demonstrates the value of this branding focus. On the surface they make cables, chargers, and batteries, just like hundreds of other sellers on Amazon or Alibaba. But their packaging is clean, their documentation is well-translated, and their support is strong.

As the Paradox of Choice has shown, when presented with too many options, a consumer will purchase less frequently. Anker’s branding overcomes the uncertainty, and they’ve ridden this trust to become the dominant accessories vendor very quickly.

Curation and vetting as a differentiation strategy

Self-proclaimed marketing gurus are always championing brand trust. When retail shelves feel like they need spam filters, there is a very real need for trust.

If I had to guess, I’d say that some form of certification—similar to the Twitter Verified badge, using a distributed accreditation, will prevail. It’s an interesting judo move against online behemoths, and an opportunity for a retailer to take a strong, opinionated position on products. Consumer Reports has this mantle, and clothing retailers like Frank&Oak or Shinesty embrace their focus.

Similarly, as we realize algorithms are using the digital breadcrumb trail behind us to know us better than we know ourselves, we’ll want to buck the trend. We’ll crave that which defies the machine, proving it wrong.

But as algorithms make a hundred songs, shows, pieces of art, phone cases, or myriad other goods easy to knock off and customize, we’re going to see the Fake Retail arms race escalate rapidly.