The 3 IT myths that cripple big company innovation

Quick sidenote: I’m launching a conference on business technology disruption called Pandemon.io. I’d like it if you told your friends, or…

Quick sidenote: I’m launching a conference on business technology disruption called Pandemon.io. I’d like it if you told your friends, or followed us on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. I’d love it if you signed up for our weekly newsletter, which we’re packing with useful stories and interviews with our speakers. And I’d be absolutely ecstatic if you bought a ticket and joined me next February in Panama, so we can discuss things like this in person.

To survive the Great Dying that digital channels have caused, big companies need to innovate, usually through software, data, sensing, and automation. And yet the majority of innovation initiatives fail horribly. That’s partly because the metrics widely used to score IT today — budgetary compliance, vendor count, and cost-of-IT-per-employee — are exactly wrong if you’re trying to build adaptive, connected businesses.

That’s a broad, sweeping statement. So I’m going to take a while to unpack it properly.

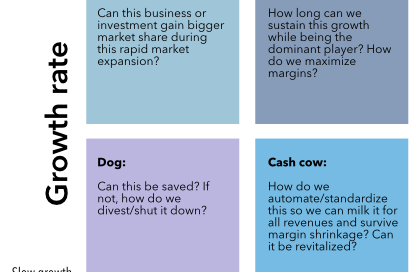

The BCG box

Every business student learns about the BCG box. It’s a consulting tool that helps managers plan product strategy. It classifies products or portfolio companies into one of four categories — stars, question marks, dogs, and cash cows — according to their market share and growth rate.

Big firms milk the cash cows (large market share, slow growth) and this delivers most of their profits. But they also have to innovate by investing in question marks (small market share, fast growth) in the hope of turning them into stars (large market share, fast growth.)

Stars and question marks grow quickly because they innovate, finding a new advantage, untapped market, or nascent offering. It’s the expansion from nothing—a pure, greenfield market to a saturated one — that provides rapid growth. It happens when the company finds a new product, or a new market, or a new go-to-market method. In other words, it happens when the company innovates.

Three kinds of innovation

Innovation is manifold, but we can break it down into three basic types: Product, business model, and operations.

Technological (product) innovation

If you say “innovation” to someone, they’ll usually think of a new, disruptive product that was created through invention. This is the what of innovation, defining what product or service you’re delivering.

Old lightbulb, from Joi Ito. (https://www.flickr.com/photos/joi/4053676608)

Many successful businesses are based on incremental technological innovation—better soap, cleaner cars. Truly new technological innovation, on the other hand, is far less common. When it does occur, it gives us the light bulb, the airplane, the telephone, the antibiotic, or the transistor—genuinely new offerings created through research and development that trigger a landslide of follow-on products because of how they change the economics of possibility.

Business model (market) innovation

Business model innovation changes how the firm reaches a market. It encompasses the go-to-market strategy, including customer acquisition or pricing. It’s about who the customer is, which depends on channel, pricing, and other front-office, customer-facing factors.

When Tupperware held home parties to sell its products rather than choosing a retail channel, it was a new sales model.

When Salesforce.com sold CRM to the sales team and delivered software via the web for a recurring monthly rate, it was a new business model.

Even James Watts’ steam engine included business model innovation when he charged customers a usage fee based on energy produced by the engines.

Operational (method) innovation

Operational innovation alters the structure of the company’s processes and norms, and even the company itself. It’s new training, new compensation schemes, and new processes. It’s innovation in how the business operates.

When Google or Huawei changed its financial structure to ensure that employees had an ongoing interest in the business, this was an operational innovation.

When multi-level marketers relied on salespeople to recruit other salespeople, they were innovating organizationally.

When UPS realized that having drivers turn right whenever possible lowered delivery times significantly, it was innovating organizationally.

As more and more of a business is run automatically, from algorithmic risk management to robotic factory floors, organizational innovation is often driven by the development and configuration of back-office software.

Rover robotic factory, by Spencer Cooper. (https://www.flickr.com/photos/spenceyc/7481166880)

No innovation is an island

Change seldom occurs along only one kind of innovation. It takes a mix of what, who, and how to innovate successfully:

The transistor needed consumer offerings to really thrive.

Salesforce had to invent new technology to make monthly on-demand pricing work.

James Watt didn’t invent the steam engine; rather, he dramatically improved it. But we know Watt’s name because his business model innovation succeeded. He and his partner were consummate marketers, coining the term “horsepower” to give people a way to talk comfortably about steam power.

Innovation is the lifeblood of organizations. It not only finds them new things to sell, and new people to whom to sell them; it makes those organizations more efficient, improving margins.

Sustained innovation is an unbeatable competitive advantage.

Can large companies innovate?

Certainly, there are some great examples of big firms that have reinvented themselves, but the data says they’re the exception, not the rule. Harvard’s Clay Christensen has described this in detail in The Innovator’s Dilemma and its sequels: Large incumbents fail to adapt and innovate into new business models.

And it’s getting worse.

The number of years a company remains on the Fortune 500 or S&P 500 has dropped precipitously in recent decades. And innovation efforts by those companies fail nearly all the time — the Corporate Strategy Board puts the chance of failure at 95%; Christensen says it’s as high as 99%.

So why the sudden dying?

Innovation, in modern organizations, is chiefly a digital matter. Most companies’ product, market, and business model changes have happened on the backs of an always-connected digital platform. The digital age is triggering a mass extinction of incumbents, and a Cambrian Explosion of new businesses.

Removal of barriers to entry

One reason the last half-century has been so tumultuous for big firms is that the move from physical to digital channels has eroded many of the traditional barriers to entry on which such firms relied.

Customer-facing digital channels circumvent middlemen, and allow much of the sales process to be entirely automated. In the back office, automation of logistics, suppliers, and platforms has replaced capital expenses with just-in-time delivery and pay-as-you-go contracting.

There was nothing technologically new about Netflix’s product when the company started. DVDs had been on the market for a decade, and the US postal service was a hundred years old. Even websites were relatively mature. So a service in which you visited a website and had a DVD mailed to you wasn’t technological innovation. But it was an innovative business model, with no late fees and a flat monthly rate, and a long-tailed catalog that included even obscure films unavailable elsewhere.

Cycle time beats scale

There’s another reason a move to digital has wide-ranging effects: Digital systems can learn and improve. Humans are bad at recording what they do. Software has no choice but to do so. So as more of the enterprise becomes digital, more of its performance can be analyzed. Smart organizations learn from this digital exhaust, improving and iterating. As a result, speed of iteration, rather than scale, has become a competitive advantage.

When Tesla updated its electric cars with new software, it significantly accelerated the arrival of self-driving vehicles. The ability to push code to an entire line of cars — and to then learn from those cars’ performance so they improved significantly in their first two weeks of driving — was unprecedented in the automotive industry.

Automation and economics

Recent employment data from economists show that despite a recovery by Western economies, jobs aren’t returning. Or rather, they are—absent those that are repeatable or easily automated.

We spent fifty years deploying computers and software into our companies; now, companies are reaping the profits: Reduced headcount, direct customer contacts, and so on.

But where humans were trained to repeat a task, and rewarded for their ability to so — requiring costly training to change their behaviour — software can be rewritten to change behaviour quickly, consistently, and at scale.

Uber was a transportation company. Then, with a software update, it turned its drivers into a food delivery service. There was little training needed, because the smartphone app that Uber workers used walked them through the process. Uber pushed new job descriptions to its workers overnight.

Haunted by bad metrics

Big organizations are vulnerable in the digital era because they haven’t adjusted their scorekeeping to the new rules.

These organizations use processes that worked well in defended, large-scale, industries where well-defined processes and rigid organizational structures ensured consistency.

Specifically, they’re told to:

Focus on IT efficiency

Reduce the number of suppliers

Predict, and deliver, long-term budgets

Those goals are exactly wrong for a digital era.

Lowering IT per employee as a goal

Information Technology has traditionally been a cost center in companies. Businesses hire consultants to assess the cost of IT throughout the company, including both spending and support, and then divide this amount by the number of employees in order to calculate a cost of IT per employee. The IT organization is rewarded for its efficiency in keeping this number as low as possible.

In a digital world, this is entirely wrong. If technology is a competitive advantage, investing in it should be rewarded. And if the addition of automation reduces the number of employees performing repetitive work, then the math looks even worse, because one must now divide a higher IT investment by fewer employees.

Is the ideal company one with a single human, managing tireless, high-margin algorithms and robots? Because that’s a company with a very high IT cost per employee.

Long-term capital budgets

A business exerts force through the deployment of capital. The annual budgeting cycle is a ritual of the corporate job, with the entire organization predicting how much, and for what, capital will be used. It’s demanded by capital markets, who value predictability: Miss your target, and the stock price goes down.

But planning is a liability in an adaptive market. The notion of long-term plans came from a world where feedback took months or years. Before digital channels, companies relied on consultants, focus groups, and test markets to evaluate an idea. Today, they can deploy products and collect feedback in near real time. Yet despite the dramatic acceleration of feedback cycles, capital planning hasn’t kept up.

Startups budget and analyze using cohorts — users of the latest product iteration; buyers from the most recent marketing campaign; customers who learned about the offering via a particular channel. This approach recognizes that the product or service they make is fungible, constantly changing, and always being improved.

The capital planning cycle of large organizations runs counter to the dynamic, transient nature of digital businesses. It rewards prediction rather than adaptation, and in so doing, encourages employees to misread the results of their actions in the hopes that their predictions will be confirmed.

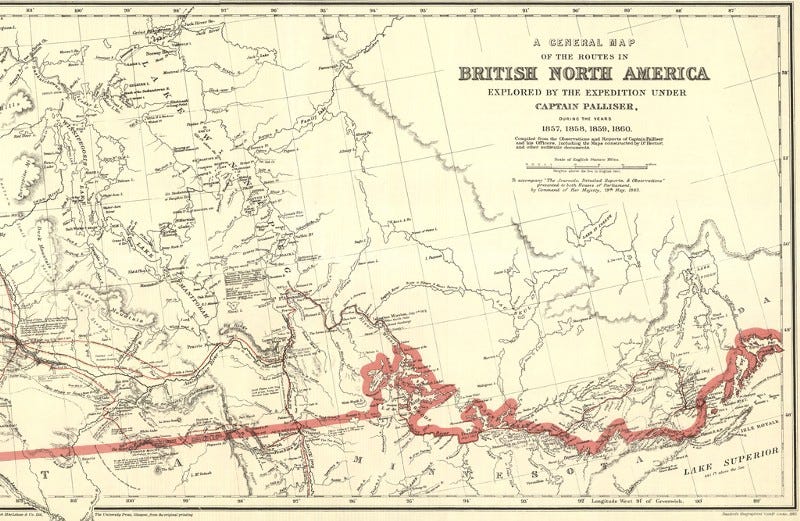

Route map by Wyman Laliberté (https://www.flickr.com/photos/manitobamaps/2211818555)

This is one reason Eric Ries is founding a stock exchange that rewards long-term thinking; it’s also why Amazon, having trained investors not to expect predictable quarterly returns, is free to innovate more aggressively than almost any other public company today.

IT monoculture

Few organizations can do all their own innovating. A big company needs fresh blood, in the form of technology, ideas, and employees. Yet just as IT is rewarded for cost-cutting, so it’s given targets to reduce the number of vendors on which the company depends. The initiatives are well-intentioned — on the premise that many vendors means more complexity and challenges with interoperability.

Unfortunately, encouraging a reduction in vendor count, rather than focusing on the real problems of complexity and interoperability, has significant negative consequences:

New suppliers have to navigate Byzantine procurement processes, starving the organization of access to innovative tools or products.

Existing suppliers broaden their offerings to the point where they become jacks of all trades, but masters of none. Big, monolithic suites for Enterprise Requirement Planning, office productivity, Human Resource management, Business Intelligence, or other widespread functions become the norm. Vendors commit to a long-term roadmap to satisfy the requirement for fewer suppliers, and deliver a weak offering as a result.

Companies get locked into software and tool stacks that are “too big to fail,” hiring consultants to keep the software working.

A multi-vendor model that focuses on interoperable, simple interfaces and cultivating relationships with several interchangeable providers gives the company better bargaining power, keeping suppliers honest and prices down.

Consolidation is commendable—and even necessary—when it reduces complexity and lowers training costs. But a digital business is a networked one. Limiting IT biodiversity has significant negative impacts, because it targets vendor count rather than complexity, which is the real source of the problem. Reducing vendor count stifles your ability to experiment and learn.

Instead, IT and purchasing should be encouraged to standardize interfaces — between users and applications, or between one piece of software and another — instead of using vendor count as a proxy metric for integration and functionality.

Conclusions

Clearly, companies need to innovate along product, market, and method if they’re to survive. And in a digital era, innovation often falls to the IT department.

The problem is that, for a long time, technology has been seen as a cost of doing business. Today, technology is the business. And yet the metrics widely used to score IT today — budgetary compliance, vendor count, and cost of IT per employee — haven’t changed to reflect this. They’re exactly wrong if you’re trying to build adaptive, connected businesses that will survive and thrive.

Cricket scoreboard by Craig Sunter. (https://www.flickr.com/photos/16210667)

Ultimately, companies need to realize that they’re playing a new game, with new rules, in a digital era. And if it’s a new game, then they have to fundamentally change how they keep score if they want even a hope of winning.